Published: August 29, 2023 on bioRxiv

DOI: 10.1101/2023.08.28.555077

Sleep is one of those universal experiences—every animal does it, from tiny worms to humans. But here's the thing: we've been defining sleep differently across species, and we've been missing something big. In mammals, we know about REM sleep (those rapid eye movements during dreams), but what about fish? Do they have REM? When did REM sleep actually evolve? These are the questions that drove our research.

The classical definition of sleep in zebrafish and other simple organisms was pretty straightforward: periods of immobility with increased arousal threshold. That's it. But we had a hunch there was more to it. So we built a system to watch zebrafish sleep like never before—high-resolution imaging, 24-hour monitoring, tracking every eye movement and body twitch. And what we found completely changed how we think about sleep evolution.

The Discovery: Two Sleep States, Not One

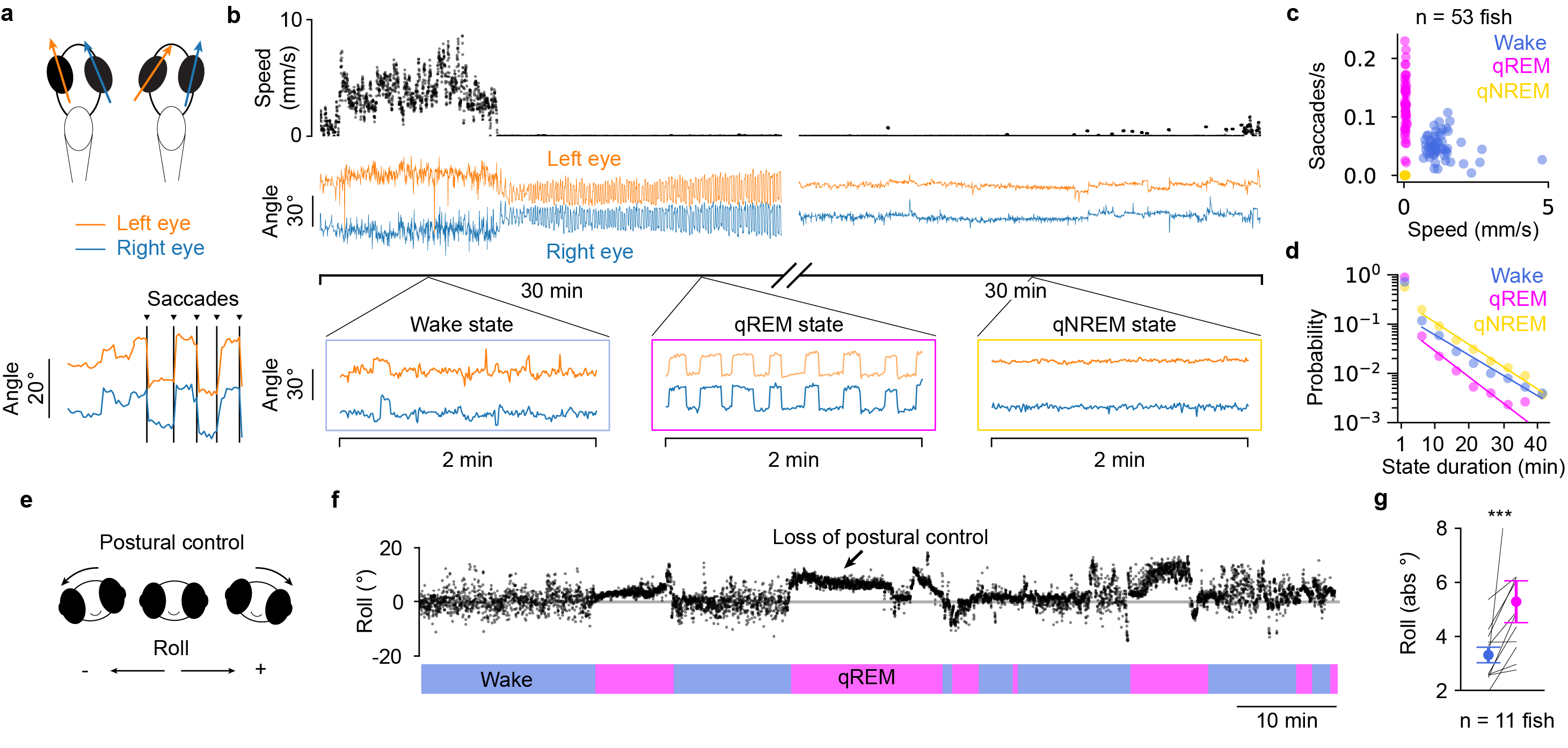

When we started watching larval zebrafish sleep, we expected to see what everyone else had seen: periods of quiet quiescence. But as we zoomed in and tracked eye movements with unprecedented resolution, something remarkable emerged. The "sleep" we thought was one uniform state was actually two completely distinct states.

One state had rapid eye movements—just like REM sleep in mammals. We called it qREM (quiescent REM). The other state had no eye movements—similar to NREM sleep. We called it qNREM. This was the first time anyone had clearly identified REM-like sleep in fish, and it was a game-changer.

But here's where it gets really interesting. These weren't just slightly different states—they were fundamentally different. The eye movements during qREM weren't random twitches. They were organized, rhythmic, and persistent. And when we looked at the brain activity, we saw something that challenged everything we thought we knew about sleep.

A True Sleep State: Low Arousal, Not Vigilance

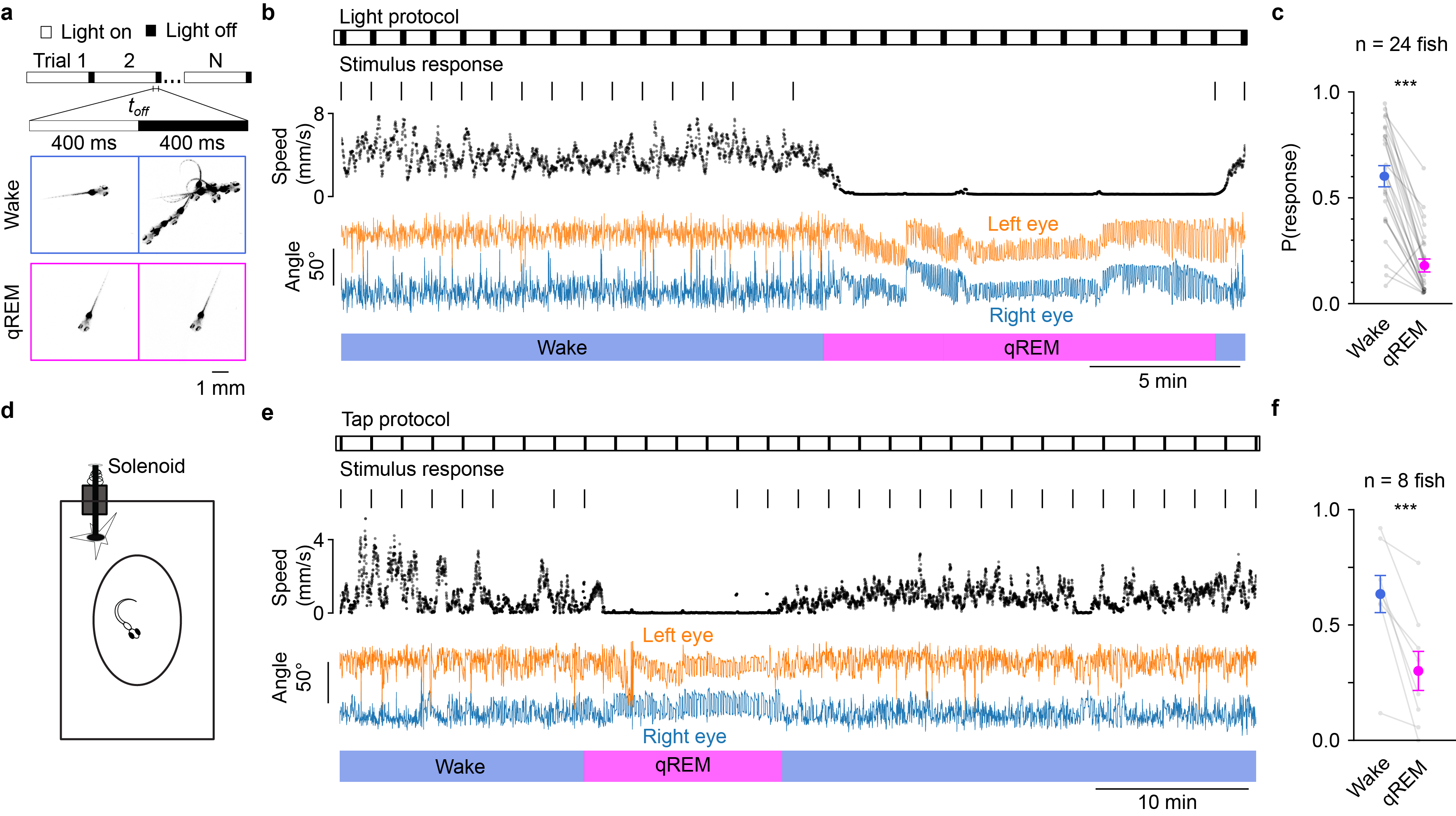

One critical question we needed to answer was whether these quiescent states were actually sleep, or just periods of low activity while the fish remained vigilant. To distinguish between sleep and quiet wakefulness, we measured arousal thresholds—how much stimulation it takes to wake the fish up.

Our measurements showed that during both qREM and qNREM, zebrafish required much stronger stimulation to wake up compared to when they were awake. This wasn't just quiet behavior—these were genuine sleep states with reduced responsiveness to the environment. The fish weren't just sitting still and watching; they were truly asleep, with their brains in a fundamentally different state.

Testing the "Scanning Hypothesis"

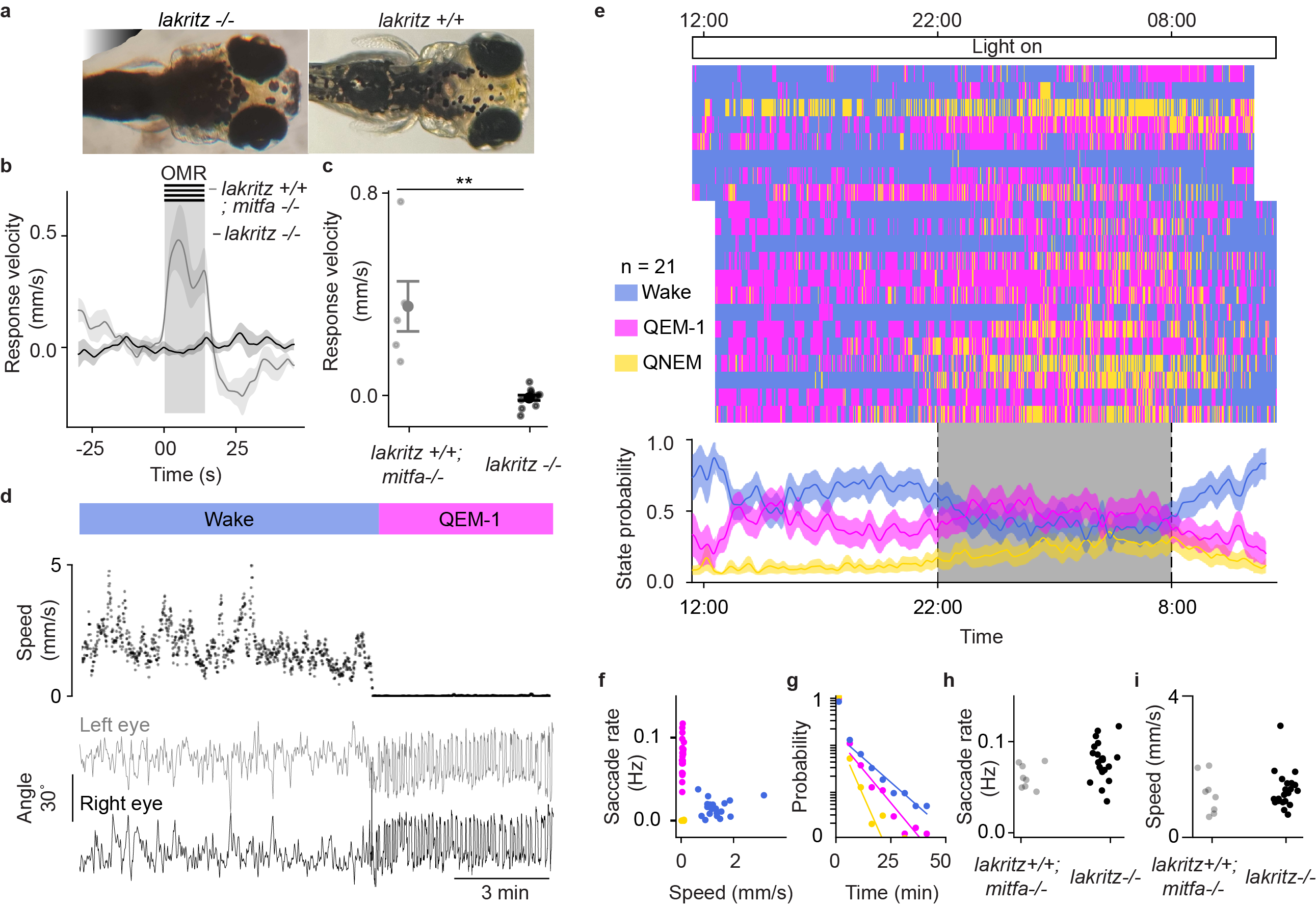

One of the oldest theories about REM sleep is the "scanning hypothesis"—the idea that those rapid eye movements are our brains scanning internally generated visual imagery (like dreams). It's a compelling idea, but we wanted to test it. What happens to REM sleep in animals that have never seen anything?

We worked with congenitally blind zebrafish—fish that were born without the ability to see. If the scanning hypothesis was correct, these fish shouldn't have REM sleep. After all, what would they be "scanning" if they've never experienced vision?

The results were clear: blind fish still had REM sleep. This was a major finding. It meant that REM sleep wasn't about scanning visual imagery. Instead, we think it's about something more fundamental—keeping the eye movement systems active and balanced during rest. It's like maintenance mode for your motor systems, ensuring they don't degrade during long periods of inactivity.

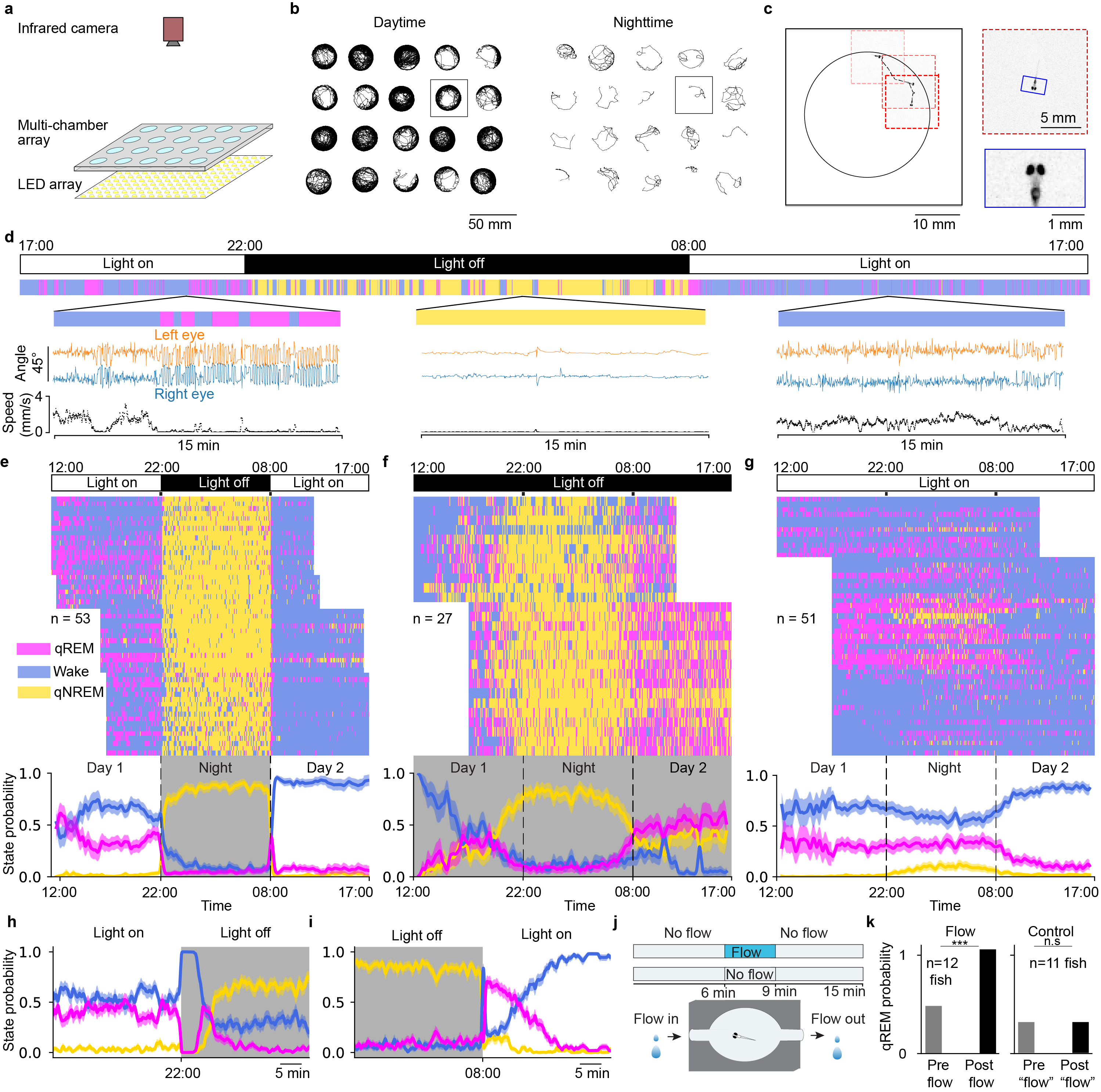

Sleep Across the Day: Circadian Organization of States

Sleep doesn't happen in isolation—it's organized across the 24-hour day-night cycle. We wanted to understand how qREM and qNREM states are distributed throughout the circadian cycle. Do they follow patterns similar to mammalian sleep? How do transitions between states change from day to night?

What we found was a sophisticated organization of sleep states across the day and night. The distribution of qREM and qNREM followed circadian patterns, with clear differences in how these states were organized during light and dark periods. This circadian regulation of sleep states suggests that the two-state sleep architecture in zebrafish is not just a simple on-off switch, but a complex, temporally organized system that adapts to the day-night cycle.

What the Brain Reveals: Dynamic Trajectories, Not Fixed Points

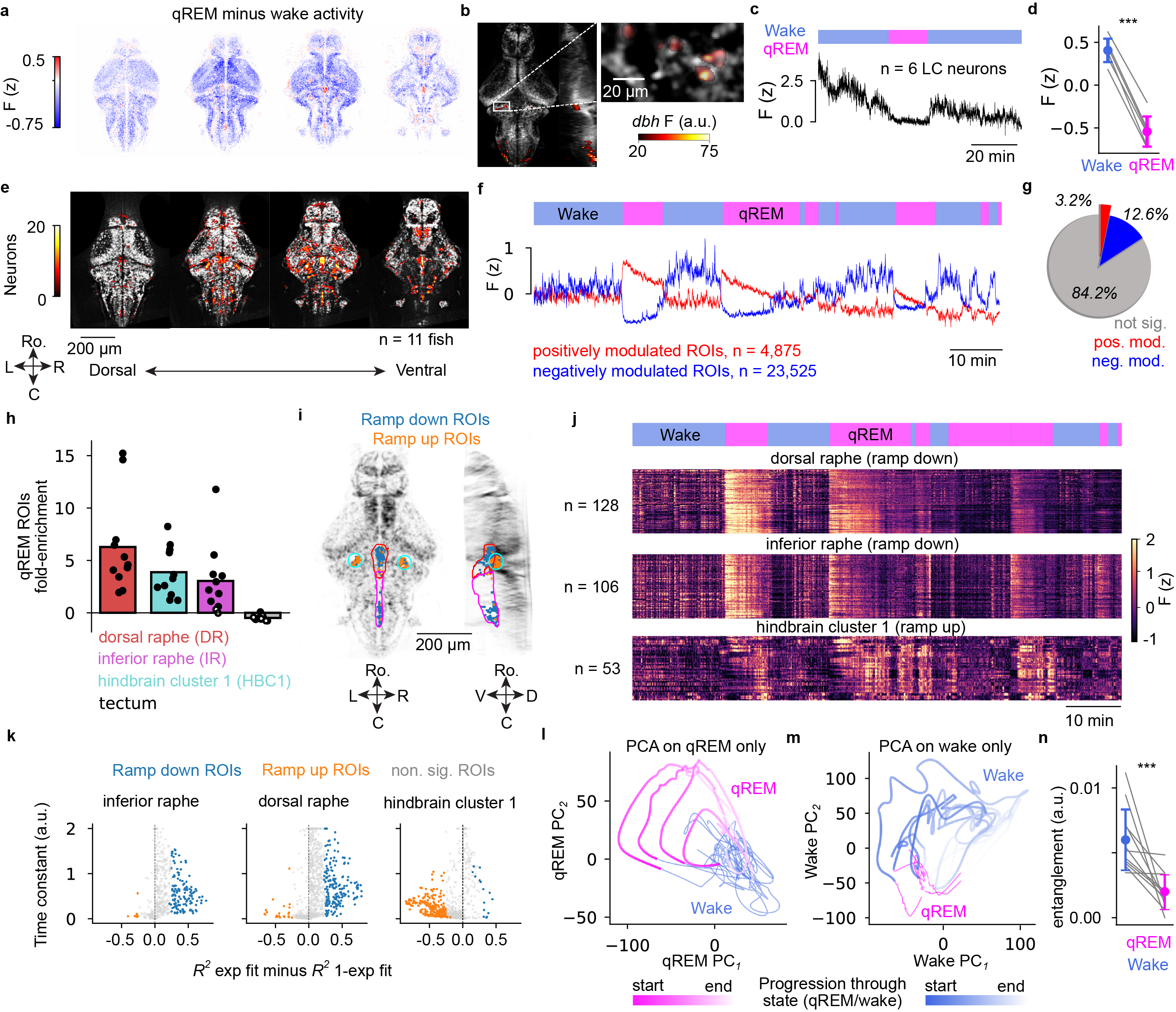

While we were watching behavior, we were also imaging the entire brain at cellular resolution. This gave us an unprecedented view of what's happening in the brain during these sleep states. And what we saw was beautiful and surprising.

Previous work in simpler organisms like C. elegans suggested that during sleep, neural activity collapses to a "fixed point"—essentially, everything quiets down to a single stable state. But that's not what we saw in zebrafish. During qREM, the brain's activity wasn't collapsing—it was flowing along smooth, committed trajectories through state-space.

Think of it like this: instead of the brain shutting down to a single point (like turning off a computer), it's more like a carefully choreographed dance. The neural activity moves in organized patterns, following specific paths. This suggests that sleep in vertebrates isn't just about rest—it's an active, organized process with its own internal logic.

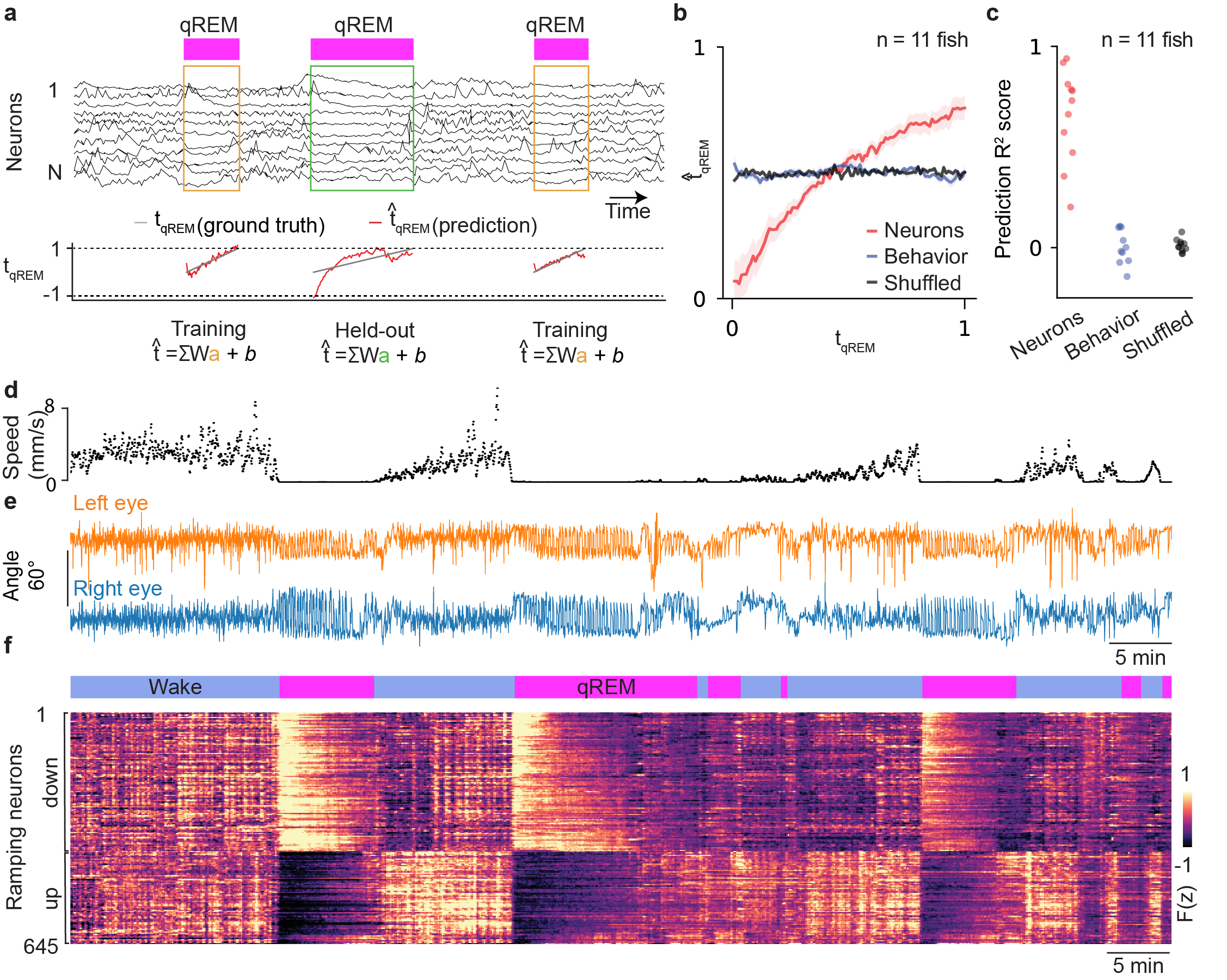

Time Encoded in Neural Activity: Decoding Temporal Structure

The organized trajectories we observed during qREM raised an intriguing question: does the brain maintain a sense of time during sleep? Can we decode temporal information from the neural population activity? We tested whether the patterns of neural activity during sleep contain information about elapsed time within a sleep episode.

Remarkably, we found that we could decode elapsed time from the neural population activity during both qREM and qNREM states. This means that the brain maintains a temporal representation even during sleep—the neural trajectories aren't just random paths through state-space, but contain structured information about how much time has passed within a sleep episode. This temporal encoding suggests that sleep states have an internal temporal structure, with the brain tracking time even when disconnected from external cues.

What This Means: Rethinking Sleep Evolution

So what does all of this tell us? First, REM sleep is much older than we thought. It didn't emerge between fish and reptiles—it was already there in early vertebrates. This pushes the evolutionary origin of REM sleep back hundreds of millions of years.

Second, REM sleep isn't about dreams or visual imagery. The fact that blind fish still have REM sleep tells us it serves a more fundamental purpose—maintaining motor systems, particularly oculomotor systems, during rest. This is probably why REM sleep is so important across species.

Third, sleep in vertebrates is more complex and active than we realized. It's not just the brain "turning off." It's an organized, dynamic process with its own internal structure. The brain during sleep isn't idle—it's actively maintaining and organizing itself.

The Bigger Picture

This work changes how we think about sleep in fundamental ways. For sleep researchers, it provides a new model system to study REM sleep—zebrafish are easier to work with than mammals, and now we know they have the same basic sleep architecture.

For evolutionary biologists, it fills in a crucial gap in our understanding of when and why REM sleep evolved. And for anyone interested in how the brain works, it shows that sleep is far more active and organized than we ever imagined.

But perhaps most importantly, this work reminds us that sometimes the biggest discoveries come from looking more carefully at things we thought we already understood. By watching zebrafish sleep with better tools and asking the right questions, we uncovered something that had been hiding in plain sight.

How We Did It

This work required developing new tools and approaches. We built a large-scale behavioral imaging system that could track up to 20 fish simultaneously at high resolution (20-50 μm/pixel) across full 24-hour circadian cycles. We combined this with brain-wide calcium imaging to see neural activity at cellular resolution in freely behaving animals. The analysis involved advanced machine learning and state-space methods to characterize the complex dynamics we observed.

Authors

Vikash Choudhary, Charles R. Heller, Sophie Aimon, Lílian de Sardenberg Schmid, Drew N. Robson, Jennifer M. Li

Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tübingen, Germany

Citation

Choudhary, V., Heller, C. R., Aimon, S., de Sardenberg Schmid, L., Robson, D. N., & Li, J. M. (2023). Neural and behavioral organization of rapid eye movement sleep in zebrafish. bioRxiv, 2023.08.28.555077. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.28.555077