Published: August 23, 2022 in Cell Reports

DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111202

The visual cortex is organized hierarchically. Information flows from the primary visual cortex (V1) to higher-order associative areas like the medial secondary visual cortex (V2M), creating a sophisticated network for processing visual information. But how do different cortical areas maintain their distinct activity patterns? What mechanisms allow V1 and V2M to have different firing dynamics and levels of coordination?

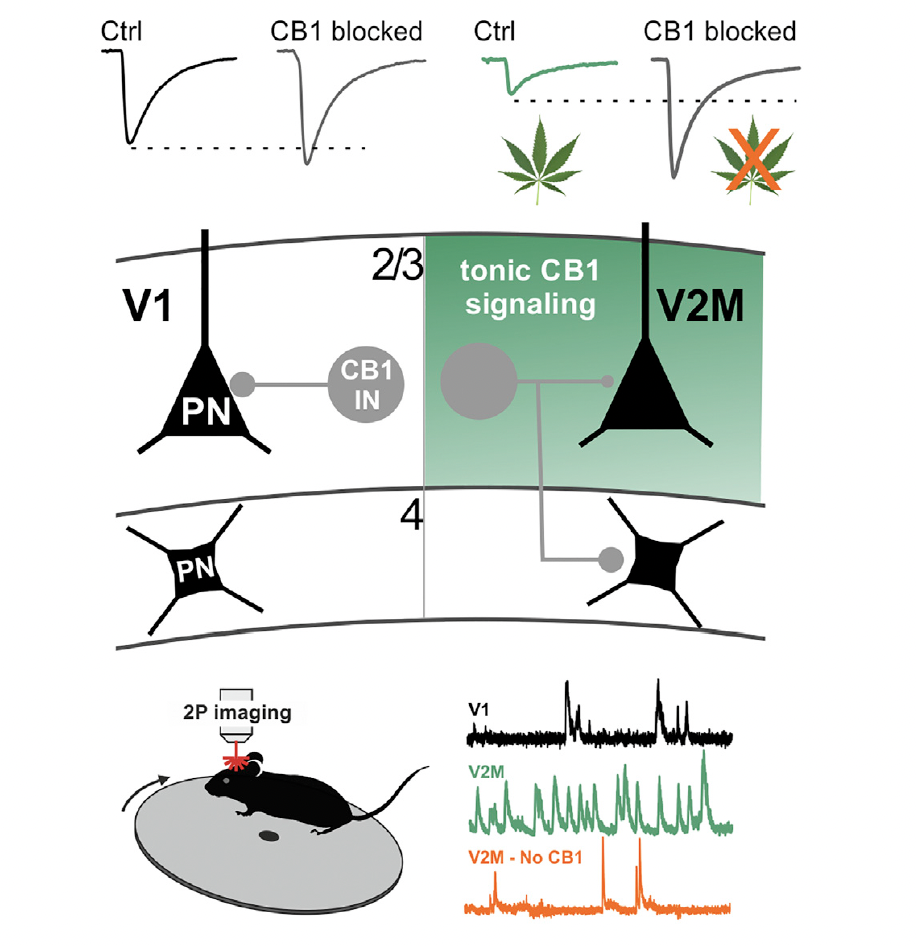

This study investigated the role of a specific type of inhibitory neuron—cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1)-expressing basket cells—in controlling neural activity across different visual areas. These interneurons target the cell bodies of pyramidal neurons, making them powerful controllers of spike generation. But their properties and roles in neocortical circuits have remained largely mysterious. My contribution to this work focused on developing and implementing an end-to-end analysis pipeline for processing two-photon calcium imaging data, from motion registration through source extraction, deconvolution, and final data analysis.

The Question: Are CB1+ Interneurons Area-Specific?

Most research on perisomatic inhibition—the inhibition that controls when neurons fire—has focused on parvalbumin (PV)-expressing basket cells. These are fast, reliable, and crucial for sensory processing. But they're not the only game in town. CB1-expressing interneurons also form inhibitory synapses on pyramidal neuron cell bodies, but their properties are very different: they're less reliable, slower, and their function in neocortex has been unclear.

We asked a simple but important question: do CB1+ interneurons work the same way in different visual areas? V1 and V2M have different jobs—V1 processes basic visual features, while V2M integrates information and plays roles in predictive processing. Could CB1+ interneurons be contributing to these area-specific differences?

The Challenge: From Raw Images to Neural Activity

To answer this question, we needed to record neural activity in both V1 and V2M using two-photon calcium imaging. This technique allows us to watch hundreds of neurons simultaneously, tracking their activity over time. But raw calcium imaging data is messy—it requires extensive processing before you can extract meaningful neural signals.

This is where my main contribution came in. I developed an end-to-end analysis pipeline that takes raw imaging data and transforms it into clean, interpretable neural activity traces. The pipeline consists of four critical stages:

- Motion registration: Living brains move. Even when an animal is head-fixed, there's motion from breathing, heartbeat, and small movements. The first step is to align all frames of the imaging data, correcting for this motion so that each pixel corresponds to the same location across time.

- Source extraction: Once the images are aligned, we need to identify which pixels belong to which neurons. This involves detecting cell bodies, segmenting them from the background, and creating regions of interest (ROIs) for each neuron.

- Deconvolution: Calcium signals are slow and blurred compared to actual neural spikes. Deconvolution transforms the slow calcium fluorescence traces into estimates of the underlying spike times, giving us a more accurate picture of when neurons actually fired.

- Data analysis: Finally, we analyze these neural activity traces to extract firing rates, correlations, and other metrics that reveal how CB1+ interneurons affect network activity in V1 versus V2M.

Each stage of this pipeline required careful optimization. Motion registration needs to be robust to different types of movement. Source extraction must accurately identify neurons even when they overlap or have weak signals. Deconvolution algorithms need to balance accuracy with computational efficiency. And the final analysis must handle the statistical challenges of comparing activity across different brain areas and conditions.

What We Found: Area-Specific Connectivity and Function

The analysis revealed something striking: CB1+ interneurons don't work the same way in V1 and V2M. Their connectivity patterns are different, and so is their function. In V2M, persistently active CB1 signaling suppresses GABA release from CB1+ basket cells, effectively reducing inhibition. But this doesn't happen in V1—the same signaling mechanism works differently.

This difference has profound consequences for network activity. In V2M, the reduced inhibition from CB1+ interneurons leads to higher firing rates but less coordinated activity among pyramidal neurons. In V1, where CB1 signaling doesn't suppress inhibition as much, pyramidal neurons fire at lower rates but with more coordination. These different firing dynamics match the different computational roles of these areas—V1 needs precise, coordinated responses to visual stimuli, while V2M benefits from higher activity levels for integration and predictive processing.

The analysis pipeline I developed was crucial for detecting these subtle but important differences. By carefully processing the calcium imaging data, we could extract accurate firing rates and correlation measures that revealed how CB1+ interneurons differentially control network activity in the two visual areas.

Capturing the Dynamics: Computational Modeling

To understand how these area-specific differences emerge, we built computational network models that incorporated the different connectivity patterns and CB1 signaling properties we observed. The models successfully captured the key differences in firing dynamics between V1 and V2M, showing that the area-specific properties of CB1+ interneurons are sufficient to explain the different activity patterns.

These models revealed that it's not just about the strength of inhibition—it's about how CB1 signaling interacts with the specific connectivity patterns in each area. The combination of reduced release probability at CB1+ synapses and increased connectivity to layer 4 in V2M creates a disinhibitory effect that boosts activity while reducing coordination. In V1, different connectivity patterns prevent this disinhibition, maintaining lower but more coordinated activity.

Why This Matters: Area-Specific Circuit Organization

This work reveals that inhibitory circuits aren't uniform across the cortex—they're specialized for the computational needs of each area. CB1+ interneurons aren't just another type of inhibitory neuron; they're part of a sophisticated, area-specific mechanism for controlling neural activity and coordination.

The finding that the same type of interneuron can have different functions in different cortical areas challenges simple models of cortical organization. It suggests that understanding cortical function requires understanding not just what types of neurons are present, but how they're connected and how their properties are tuned for the specific computational demands of each area.

From a technical perspective, this project demonstrated the importance of robust, end-to-end analysis pipelines for calcium imaging data. The ability to accurately extract neural activity from raw imaging data is fundamental to modern neuroscience, and the pipeline developed here provides a framework for processing similar datasets in future studies. By combining careful data processing with sophisticated experimental design, we can uncover subtle but important differences in how neural circuits are organized and function.